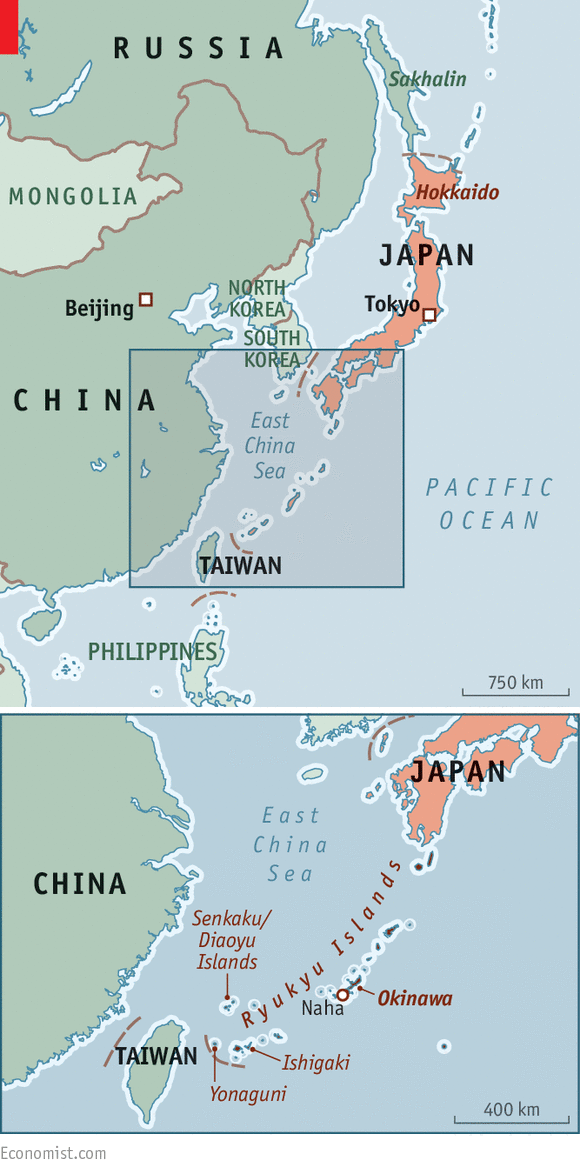

AT THIS time of year pack ice grinds the beaches of northern Japan, but in the Ryukyu Islands in the south farmers are cutting sugar cane. The Japanese archipelago spans an immense distance: from Cape Soya in northern Hokkaido a smudge on the horizon reveals Sakhalin in Russia’s Far East. From the tiny island of Yonaguni, last in the Ryukyu chain, you can sometimes make out the mountains of eastern Taiwan.

Over lunar new year the Ryukyu Islands, which together make up Okinawa prefecture, were heaving with holidaymakers. Okinawa has a growing reputation as an island paradise for all tastes. Package tours poured families from mainland China into the airport at Naha, the capital, for winter sun, duty-free malls and hearty stir fries—spam is a speciality. Some 400km farther south, a cruise ship nosed between coral reefs into the main port of Ishigaki island and disgorged Taiwanese tourists in search of the local black pearls. A few adventurers even made it to Yonaguni, where they dived among the hammerhead sharks or stood on the quay in Kubura to watch the fishermen bring in their daily haul of swordfish. The island lies in the middle of the life-giving Kuroshio current, the western Pacific’s Gulf Stream.

Among security types, Okinawa is known as a garrison island. The roar of F-15s is certainly a feature of life in Naha, but most visitors get little hint of the military presence. The sense of peace is not a figment of tourist brochures. Pacifism is hard-baked into Okinawans’ sense of themselves. Masahide Ota, a former governor, once said the main features of the Ryukyu kingdom, which was independent until Japan annexed it in 1879, were a “devotion to peace and an absence of weapons”. Okinawans love to mention Basil Hall, a naval captain who visited in 1816 and marvelled at the kingdom’s mildness, decorum and seeming lack of weapons. Hall later called on Napoleon Bonaparte in St Helena and perplexed the exiled emperor with tales of the Ryukyus. “But without arms, how do they fight?” Napoleon exclaimed.

In truth, there were arms. But squeezed between bigger neighbours, China and Japan, it suited the Ryukyuans to promote a sense of Confucian virtue. And peace is a fragile thing, even today. Just as Hokkaido once lived on a cold-war tripwire, facing the Soviet Union, so the Ryukyu Islands are caught up in East Asia’s 21st-century geopolitics. Yonaguni is little more than 100km from Taiwan, and it is hard to imagine how conflict between China and America over that country would not draw in Japan. Yonaguni is also the closest inhabited Japanese island to the Senkaku islets, which, with growing ferocity, China claims (and calls Diaoyu). On a hill behind Kubura a chain-link fence and CCTV are going up around a new base for 160 troops from Japan’s Self-Defence Forces. The base is to conduct surveillance of the surrounding seas and skies. Yonaguni has become the new tripwire.

The base was controversial among the 1,500 islanders, over two-fifths of whom voted against it. Even those in favour blame Japanese right-wingers, especially a former Tokyo governor, Shintaro Ishihara, for inflaming the Senkaku dispute. In the end, strong-arming by the central government and a promise of economic benefits from the base won the day.

More bases are planned for the southern Ryukyus. A heliport is mooted for the more populous Ishigaki, from which the Senkakus are administered. All the cement and barbed wire may even help to convince the sceptical Donald Trump that Japan is pulling its weight in its alliance with America. Shinzo Abe, the hawkish prime minister, needs little encouragement.

Few people in Okinawa think open hostilities with China are imminent, or perhaps even likely. But many resent the way geopolitical tensions and a hawkish government are spreading the curse of military encampments: previously, the southern Ryukyus had but one small radar base.

That stands in contrast to the northern end of the chain. Okinawa, with 0.6% of Japan’s land area, plays host to three-fifths of all America’s facilities in Japan and half of the 53,000-odd American troops. Nearly a fifth of the main island is given over to American bases. For 70 years, Okinawa has been the fulcrum of America’s military presence in Asia.

The Americans first came in the 1850s, with gunboats opening the Ryukyus as well as Japan to trade. They reappeared at the end of the second world war, fighting their way towards Japan proper. The Japanese authorities, who before the war had tried to snuff out the local culture and language, mounted a furious defence in Okinawa to save the “home islands”. Roughly a quarter of Okinawans died, caught in the brutal fighting. The survivors emerged to find Americans their masters. America then fostered not just a taste for spam, but also a distinct local identity, hoping to dampen Okinawans’ desire to rejoin Japan. When Okinawa did revert in 1972, the bases stayed. The resentment feeds an Okinawan sense of separateness, and even a tiny independence movement.

Spam today, spam tomorrow

In elections, Okinawans vote overwhelmingly for candidates opposed to the American bases and to the noise, accidents and crime associated with them. This week the governor of Okinawa, Takeshi Onaga, flew to Washington to convince the Trump administration not to carry on with the construction of a hugely unpopular new base for American marines. Yet the American defence secretary, James Mattis, was also on his way to Japan, reportedly to emphasise the firmness of the alliance and the need for Japan and America to work together.

In Tokyo Mr Abe’s allies speak witheringly of Okinawans, but shy away from suggesting bigger bases in the heartland. Okinawa considers itself doubly colonised, by both Japan and America. Sadly, with regional tensions only likely to rise, its continued subjugation seems assured. And the curious mix of tourist paradise and bristling fortification will grow ever more jarring.

No comments:

Post a Comment