America’s foreign bases

Go home, Yankee

The presence of American troops on foreign soil is growing more controversial

AT THE end of July the United States army announced plans to hand back 15 square miles (40 square km) of land on Okinawa to the Japanese government. This will be the biggest land return in the island, home to almost 30,000 American troops, since the United States’ formal occupation ended in 1972. The decision follows the rape and murder of a local woman and big anti-American protests in June.

Opposition to American bases has increased recently in Turkey, too. In the wake of July’s failed military coup, many Turks have accused American soldiers on the Incirlik air base of being among the plotters. Three days after the coup Yusuf Kaplan, a pro-government journalist, tweeted: “USA, You know you are the biggest terrorist! We Know All the Coups are your work! We are not stupid! #procoupUSAgohome.”

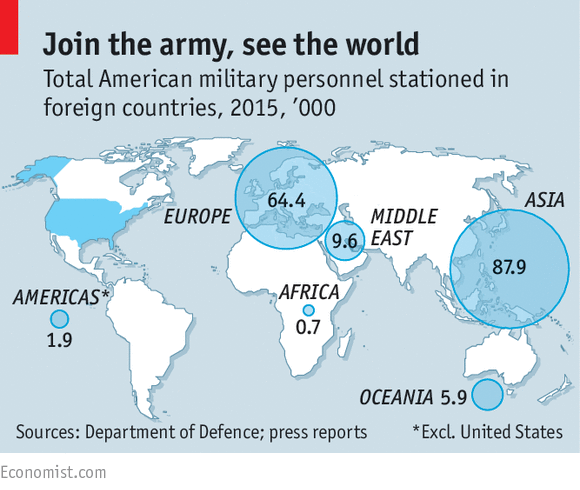

America has more overseas military bases than any other nation: nearly 800 spread through more than 70 countries. Of the roughly 150,000 troops stationed abroad, 49,000 are in Japan, 28,000 in South Korea and 38,000 in Germany; the total cost to the American government, with war zones excluded, is up to $100 billion a year. For much of the 20th century, overseas military facilities were justified as a bulwark against the Soviet threat; as that faded, other reasons to stay soon emerged. Since the 1990s, wars in the Middle East have meant that countries such as Bahrain and Turkey have gained strategic importance. (American strikes on Islamic State (IS) are launched from the Incirlik base.) More recently, China’s growing naval power has prompted America to reinforce its presence in the Pacific.

Home support for foreign bases peaked a year after the September 11th attacks, when 48% of Americans thought projecting military might was the best way to reduce the terrorist threat. Today, although about the same number still believe that, 47% think it creates hatred and leads to more terrorism. (The divide falls along partisan lines, with 70% of Republicans supporting military force, and 65% of Democrats opposing.) When it comes to overseas bases themselves, though, Americans, for the most part, are “completely unaware” of them, says David Vine, associate professor of anthropology at the American University and author of “Base Nation: How US Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World”. If they consider them at all, he says, “most people would think the US military is good so US bases, wherever they are, must be a good thing”. During the presidential primaries Donald Trump, the Republican nominee, questioned the need for, and the expense of, so many overseas bases. No other candidate did.

False assumptions about the costs of funding America’s overseas military presence could, in part, explain the public’s ambivalence. According to Mr Vine, even “so-called experts within the military” believe the bases do not cost America much because foreign governments foot a large part of the bill. In reality, he explains (and according to an estimate by the RAND Corporation in 2013), keeping members of the armed forces overseas, rather than within the United States, costs between $10,000 and $40,000 extra for every man and woman involved.

Within the armed forces, an overseas posting is still seen by many as a perk of the job and one of the main reasons to sign up in the first place. “For maybe 75% of the people I talk to, travelling is the biggest thing that gets them,” says Staff Sergeant Marco Lopez, a recruiter based in Los Angeles. Another recruiter, Staff Sergeant Andrew Murray, based in Tennessee, explains that a lot of new recruits “are looking to get out of small-town Tennessee; when I tell them about my experience in Europe, they just light up.” Europe, particularly Germany, seems to be one of the most popular destinations for army recruits. The sergeants found Germans particularly friendly and welcoming; Europe’s rich history attracts some, while Sergeant Murray enjoyed being able to visit “a different city every weekend, partying and sightseeing”.

Before going overseas, American troops are given a detailed briefing on what to expect and how to behave. Sergeant Murray says he was warned that Germans are not good at queuing, and that it was a good idea “to tone down the patriotism”; Sergeant Lopez, when stationed in Seoul, was told to avoid areas known for prostitution. Not all those enlisted take the briefings on board, as the recent events in Okinawa have made clear. Uncle Sam’s pay-cheques feed the economies of areas with army bases, but mostly through the soldiers’ patronage of night clubs and bars—which can lead to trouble.

In the past 15-20 years the Pentagon has taken steps to improve relations between its overseas outposts and local communities. Most of these have involved trying to rein in wayward soldiers. In 2006 an anti-prostitution charge was added to the United States Military Code of Justice (to the outrage of some American troops stationed in Germany, where prostitution is legal). The Department of Defence also reported an increase in the number of sexual-assault cases taken to courts martial, from 42% in 2009 to 68% in 2012. But Japan remains an outlier: within navy and marine-corps units stationed there, only 24% of those charged with sexual offences were court-martialled in 2012, the latest date for which data are available.

The United States has 85 military facilities scattered across Japan—a legacy of American occupation after the second world war. Three-quarters of the territory occupied is on the string of islands making up Okinawa, along with more than half of the 49,000 military personnel. Okinawans resent the heavy burden they have shouldered, as well as the American presence itself—particularly the brothels. These were deliberately set up for United States troops and remained legal on the island until 1972, 14 years after they were banned in the rest of the country. The protests in June over the most recent rape victim were the latest in a long line of anti-American demonstrations. The largest came in 1995, when 85,000 Okinawans took to the streets following the gang-rape of a 12-year-old girl by three American soldiers.

In the past, the presence of American troops has also sparked more general protests. During the cold war West Germany played host to more American military facilities than any other country, up to 900 by some definitions, incorporating schools and hospitals as well as sports complexes and shopping centres. Local communities protested against the noise and disruption from constant military manoeuvres. Opposition reached its peak at the end of the 1980s, fuelled further by growing anti-nuclear sentiment. Leftist groups, the Red Army Faction and the Revolutionary Cells also launched violent attacks against American army headquarters and kidnapped military personnel, objecting to the mere physical presence of America in their country.

Miss you, miss you not

Almost 30 years later, the withdrawal of American troops from Germany is well under way: in 2010 the army announced it was handing over 23 sites to the German government. “We don’t miss them, but we weren’t wanting them to leave either,” says Hans Schnabel, a business-development manager in charge of converting old army bases in the Bavarian city of Schweinfurt, where up to 12,000 soldiers and their families were stationed before it closed in September 2014. After the cold war resentment in Germany towards the bases, and American forces in general, became more subdued; recent protests, such as one in June outside the Ramstein base against alleged support for drone operations, are fewer and quieter. At Schweinfurt, says Mr Schnabel, local people even think of the base with nostalgia: they are building an “American house” to remember those stationed there, and the streets around the new housing development (once the barracks) will be given names such as California Strasse and Ohio Strasse.

In contrast, America’s military presence in Turkey, as in Okinawa, is still a focus of thriving anti-Americanism today. The relationship began well enough: in 1946, when the USSMissouri sailed into Istanbul, the show of American might was warmly welcomed. It foreshadowed Turkey’s accession to NATO six years later and the stationing of American troops across the country. American enclaves in Ankara, and sailors’ weekend jollies in Izmir and Istanbul, contributed to a change in public opinion. By the end of the 1960s “Go home Yankee” signs greeted disembarking American sailors and soldiers. In the 1970s, as in Germany, leftist revolutionary groups resorted to increasingly extreme tactics in their attempts to “liberate” Turkey from American imperialism: the Turkish Revolutionary Army abducted four American airmen in March 1971 and three NATO engineers the next year.

Since then, America’s military presence in Turkey—though far less substantial than in Japan—has been seen by many as an unwanted encroachment on Turkey’s independence. In 2003 Turks protested against the war in Iraq and proposals for America to station military personnel at the Mersin naval base. When the USS Stout docked in Bodrum in 2011, members of the Turkish Communist Party stood on the shore chanting anti-American slogans. Three years later, in two separate events, members of the Turkish Youth Union targeted American sailors and NATO soldiers in Istanbul, putting white sacks over their heads and throwing red paint over them. A similar incident occurred at Incirlik air base in April this year. Even a visit by President Barack Obama, during his trip to Turkey in 2009, drew crowds of angry protesters shouting “Yankee go home” and “Get out of our country.”

The latest attacks against America’s military presence in Turkey, however, mark a shift. Since the Syrian war broke out, the United States has increasingly used the Incirlik base to support the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), implying that it might also support an autonomous Kurdish state carved out of Turkey. America and its armed forces have long featured in conspiracy theories, too, particularly those involving Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic cleric living in self-imposed exile in the United States. The recent attempted coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is proof to many Turks of a Gulenist-American alliance, and of the subversive influence of American armed forces in the country. The closure of Incirlik air base for a short time immediately after the coup added fuel to the conspiracy theories. Mr Erdogan himself seems to be using America as a scapegoat, intentionally ramping up hostility towards the personnel stationed there.

The strategic importance of Incirlik for America’s campaign against IS means that keeping American combat boots on Turkish soil is more in America’s interests than Turkey’s. But given that anti-Americanism in Turkey is one of the few sentiments uniting an increasingly undemocratic and destabilised country, American troops will have to tread carefully: they are likely to become bigger, not smaller, targets as internal tensions mount.

In many other countries both sides, despite sporadic differences, have an equal interest in Americans staying. After the protests in 1995 in Okinawa, America and Japan agreed to close Futenma, the marine air base in the overcrowded city of Ginowan, and to build a new facility in Henoko, a fishing village. The plan failed to appease locals—who re-elected anti-base politicians such as Takeshi Onaga, Okinawa’s governor, in June’s local elections—but Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister, is pressing ahead with it anyway.

He has particular reason to try to smooth tensions between the two sides. North Korea’s flaunting of its nuclear weapons and China’s aggression in the South China Sea mean his plans for strengthening Japan’s military defences must go ahead, and the United States’ armed forces are an essential part of this. Some 47% of Americans would agree with Mr Abe: they are in favour of extending America’s military presence in Asia to counter Chinese power. But 43% are opposed. America, despite what its enemies sometimes suppose, is never really thrilled to be the world’s policeman—especially if the world proves ungrateful.

No comments:

Post a Comment