David Axe

U.S. is building up forces on strategic islands in the Far East

Aviation Week

April 27, 2007

U.S. Air Force KC-135R Stratotanker angles toward Kadena Air Base from the sea, its four turbofans idling as it flares for landing. A Navy P-3C Orion patrol plane is visible through the bluish smoke as the tanker's tires touch the runway. The P-3C accelerates to its place in a long line of aircraft waiting to take off, including F-15C Eagle fighters and, for the first time outside the U.S., brand-new F-22A Raptor stealth fighters on a three-month deployment from Langley, Va. One by one the fighters roar into the bright blue sky over this Japanese island, heading for an ocean range where they will practice aerial combat and tanking, preparing for the day when they might be ordered to sweep the skies of Chinese or North Korean warplanes as part of the defense of Taiwan or a bombing campaign against Kim Jong Il's nuclear facilities.

Thousands of miles from Okinawa, U.S. ground forces are fighting insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan, conflicts that have effectively monopolized the nation's deployable land power. But in the Pacific, the Pentagon's focus is on the opposite end of the spectrum of potential conflict: The perceived threats here are large industrial militaries equipped with ships, aircraft and tanks, whose commanders develop strategies for traditional goals like capturing territory. The 300,000-strong U.S. forces arrayed to defeat these threats are, in contrast to those fighting in the war on terror, primarily air and naval.

Coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan increasingly promote soft strategies such as reconstruction, humanitarian aid and foreign security-force reform in order to win a conflict with relatively little direct combat. In the Pacific, by contrast, improving U.S. forces means spending big dollars to outfit them with the latest hardware while also expanding the sprawling bases that will serve as "fortress hubs" for future operations in the region. In coming years, Pacific Command is gaining three permanent F-22 squadrons, 16 C-17 Globemaster airlifters, two additional nuclear attack submarines and the first Littoral Combat Ships, in addition to its present forces.

"Arms buildup? I wouldn't use that language," says Air Force Maj. David Griesmer from Pacific Command, which has its headquarters in Hawaii. "There's certainly an acknowledgment that Pacom is half the world. These capabilities need to either go on one side [of the world] or the other. The Asia-Pacific region is growing. It's the way of the future. There's a large amount of economic activity." Plus, he adds, "The six largest militaries are in this area," a reference to China, the U.S., Russia, India, North Korea and South Korea.

To many observers, in fact, the future looks a lot like the past--the Cold War, but with an Asian flair.

Indeed, the linchpin bases for U.S. Pacific strategy are both prizes from World War II to which the Cold War was a grand corollary. Okinawa, Japan's southernmost prefecture and the site of Kadena AB among other U.S. installations, was wrested from Japan during a three-month struggle in 1945, during which at least 200,000 people died. Guam, the other major U.S. hub in the Pacific, was invaded and occupied by Japan between 1941 and 1944. More than 20,000 people died when the U.S. retook the island.

The locations and geographies of the outposts dictate their roles. Despite being crowded and something of a political hot potato, Okinawa's proximity to the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula--just over an hour's flight to either--and the sheer size of Kadena, one of the largest U.S. air bases in the world, means it is indispensable as a base for short-range aircraft that must react quickly.

At Kadena, alongside 7,000 personnel, the USAF has permanently stationed more than 50 F-15s plus tankers, E-3 Sentry radar planes, HH-60G rescue choppers and Special Forces aircraft, all belonging to the 18th Wing. Elsewhere on Okinawa, the Marines fly F/A-18 Hornet fighters, tankers and helicopters. RC-135 Rivet Joint spy planes and EA-6B Prowler jammers are frequent guests. The Navy's six Pacific Fleet aircraft carriers, including the USS Kitty Hawk (CV-63), homeported in Yokosuka, Japan, are also regular visitors to the area with their Hornets, F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, E-2C Hawkeye radar planes and helicopters. And in a crisis, perhaps hundreds of U.S.-based fighter aircraft would converge on Okinawa.

"Because of our capability to stage forces out of here--this is a huge runway--we do believe we have unmatched air power," says Kadena official John Monroe. "That's probably the most important thing about Kadena."

During testimony before the House Armed Services Committee, then Pacom chief, Navy Adm. William Fallon, and Army Gen. Burwell Bell, commander of U.S. forces in South Korea, seconded Monroe's assessment, announcing that U.S. Pacific forces maintain "overmatch" in the region, especially with regard to aircraft and ships. But Bell conceded that bomb and missile stockpiles were a potentially limiting factor.

That's a view the Air Force shares. Hence its investment in a 6,000-acre munitions storage area adjacent to the Kadena runway, the size of which exceeds that of many air bases elsewhere in the world. "We keep munitions for several types of aircraft because we are going to be a forward staging base," Monroe explains.

The F-22 deployment to Kadena, which began in February, is exercising the base's ability to support visiting fighter units in addition to testing the expeditionary skills of F-22 pilots and maintainers from the 27th Fighter Sqdn., which is part of the 1st Fighter Wing. And the deployment is paving the way for permanent basing of three Raptor squadrons in the region, starting with 18 jets for the Alaska-based 3rd Wing this year.

Many regions might have hosted the new fighter's first foreign deployment. But the Pacific is a perfect fit for the Raptor "because it can travel long distances," Griesmer says. The Raptor's range, while classified, exceeds that of most other fighters.

But 27th Fighter Sqdn. commander Lt. Col. Wade Tolliver says that, more than range, the Raptor's ability to penetrate air defenses--thanks to its speed, stealth and sensors--makes it uniquely qualified for Pacific duty as a trailblazer for all those follow-on forces Monroe describes. "There are a lot of countries out there that have developed highly integrated air-defense systems," Tolliver says. "The United States and its allies are used to going to a place and building up things prior to making an offensive. . . . What we need to do is take some of our assets that have special capabilities--B-2s, F-22s, F-117s--and roll back those integrated air-defense systems so we can bring in our joint forces."

From a training perspective, the Pacific is ideal for fighter pilots due to the high concentration of friendly jets for mock dogfighting, and because of the large number of tankers at Kadena and other bases. "Tanker capability is very important," Griesmer says of the Pacific. "Look at the map and see all the blue." But due to tanker shortages in the U.S. owing to the fleet's advanced age, the fighter pilots that might have to rely on aerial refueling during a Pacific surge find it difficult to keep up that perishable skill. "Normally, we tank about once a week because we're sharing tanking assets with other fighters on the East Coast," says Capt. Chris Gentile from the 27th Fighter Sqdn. But at Kadena, he and the other Raptor jockeys tank almost every day.

Distance, and its perils, define Pacific operations. Kadena's proximity to potential battlefields is an advantage for short-range fighters, but a liability too, since it's within range of North Korea's and China's tactical ballistic missiles. The U.S. Navy has deployed rudimentary sea-based missile defenses in the Sea of Japan in the form of Raytheon SM-3 Standard interceptors on board a handful of the 175 ships in the Pacific Fleet. As a backstop, in August the Army stationed a Lockheed Martin PAC-3 anti-missile battery at Kadena to protect the air base.

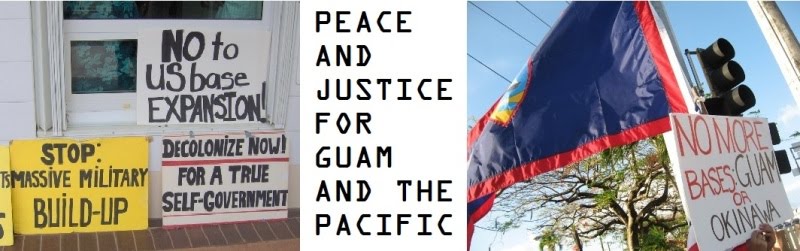

Guam, more than 1,000 mi. to the south, is protected from ballistic missiles by its distance, allowing the Army to postpone a planned PAC-3 deployment to the island to around 2012. What's more, while local political opposition has long plagued U.S. forces in Japan, the Chamorros of Guam mostly welcome the 12,000 military personnel on the island. "It may be easier for us to be there, as far as the diplomatic issue is concerned," Monroe says "but if we're in Guam, we're out of the fight" due to the distance.

This distance has shaped the force structure on Guam. For three years, the island's Andersen Air Base has hosted rotations of heavy bombers, tankers and patrol planes from the U.S., all assets with long ranges and long loiter times that mitigate the impact of distance on their operations. In February, the USAF activated the 36th Operations Group on the island to smooth the comings and goings of B-52H Stratofortresses, B-1B Lancers and B-2A Spirits. And this year, the Air Force will permanently station RQ-4B Global Hawk spy drones at Andersen. To support these aircraft plus the three attack submarines that began arriving in 2002, two more submarines that are planned and as many as 8,000 Marines from Okinawa, the Pentagon is investing up to $1 billion in construction over the next decade.

Okinawa and Guam thus fulfill complementary roles in U.S. Pacific strategy-the former as a staging base for short-range fighters, the latter as a safer, albeit more distant, base for bombers, drones and submarines.

No comments:

Post a Comment